Federal Court of Appeal Quashes Cabinet Approval of Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion

On August 30, 2018, the Federal Court of Appeal released its decision in the matter of Tsleil-Waututh Nation et al. v. Attorney General of Canada et al. In this decision, the court has quashed Cabinet’s approval of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project. This decision casts a shadow of uncertainty over the project for the immediate future. The Tsleil-Waututh Nation decision is the most recent chapter in the ongoing chronicle of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project. This blog post offers an overview of the recent history of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project and a review of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation decision.

The Trans Mountain pipeline is a project that goes as far back as the 1950s, when the pipeline began transporting petroleum products from Alberta to British Columbia and parts of the United States. As we have written in a previous blog post, in 2007, Texas-based Kinder Morgan assumed control of the Trans Mountain Project.

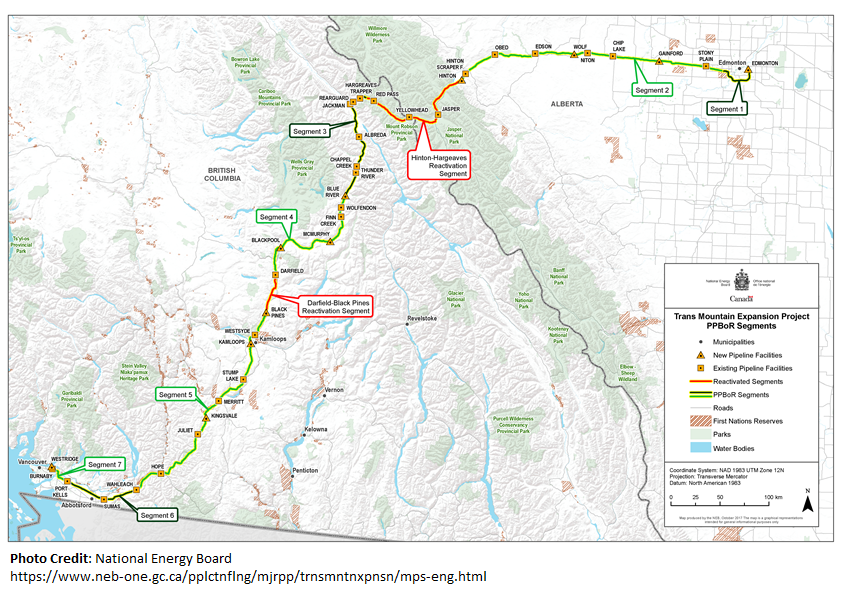

In 2013, Trans Mountain submitted an application to the National Energy Board (NEB) seeking approval for an expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline project. The Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project is a proposal to twin the existing 1,147 kilometer Trans Mountain pipeline system and to build 981 kilometers of new pipeline. The proposed pipeline system would run from Edmonton, Alberta to Burnaby, British Columbia, and ship an estimated 890,000 barrels of oil per day.

In May 2016, the NEB issued a report recommending the approval of the Kinder Morgan application, albeit with certain conditions. Acting on this report, the federal Governor in Council (Cabinet) then directed the NEB to issue a certificate of public convenience and necessity approving the construction and operation of the expansion project.

The Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project has been met with considerable opposition which challenged the project’s execution. Detractors of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion have expressed their opposition in both the court of public opinion and the court of law. As we have written in previous blog posts, a variety of groups applied to the courts to challenge the pipeline’s approval over the past few years (see here and here). More recently, the British Columbia government announced its plans to issue new regulations that will stop pipeline companies from increasing bitumen shipments through the province. As described in a recent post, in April 2018, the B.C. government submitted a reference question to the B.C. Court of Appeal regarding these recently-announced regulations.

In April 2018, Kinder Morgan announced that it would be suspending all non-essential activities and related spending on the project (read more about that announcement here). Several weeks later, however, the Government of Canada announced its intention to purchase the pipeline project from Kinder Morgan (Read more about the Government of Canada decision here).

So, what is Tsleil-Waututh Nation all about? In this case, a number of applications for judicial review were brought before the Federal Court of Appeal. These applications were heard in October 2017. The applicants included several First Nations, including the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, the Cities of Burnaby and Vancouver, and two non-governmental actors.

This case involved two discrete matters that were consolidated into one hearing.

The first matter was for the judicial review of the report from the NEB, which recommended that Cabinet direct the NEB to issue the certificate of public convenience and necessity.

The second matter was for the judicial review of the decision of Cabinet to accept the recommendation of the NEB, and to issue the Order in Council directing the NEB to issue the certificate of public convenience and necessity.

The application for review of the Board decision was dismissed. In this decision, the court held that the report of the Board created pursuant to section 52 of the National Energy Board Act was not a justiciable matter.

However, the applications for judicial review of the decision of Cabinet were granted. There were two primary grounds to challenge the decision of the Governor in Council. The first was the factual basis of decision making, and the second was the duty to consult.

With respect to the first ground of challenge, the court found that the report of the NEB was unacceptably flawed. The court found that the report did not provide the Governor in Council with pertinent information related to the project’s environmental effects. Specifically, the NEB report wrongly narrowed the scope of its environmental assessment by excluding the effect of Project- related shipping of petroleum at the pipeline’s destination. Since the NEB report forms the basis of the Governor in Council’s decision on the matter, Cabinet’s decision to direct approval was unreasonable.

With respect to the second ground of challenge, the court found that the Government of Canada failed to adequately discharge its constitutional duty to consult with First Nations. Specifically, “Phase III” of the duty to consult.

As part of Phase III, the Government of Canada was required to engage in a meaningful and reciprocal dialogue with First Nations. The court found that this did not occur. Instead of a two-way dialogue, the Government of Canada limited their mandate to listening to and recording the concerns of affected First Nations. The lack of adequate consultation also rendered the Governor in Council’s decision unreasonable.

Pursuant to these findings, the Federal Court of Appeal quashed the Order in Council directing that the NEB approve the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project. The issue of project approval has been remitted to Cabinet for redetermination, having regard to the shortcomings identified by the Federal Court of Appeal. Further, the court ordered that Phase III consultation must be re-done.

The decision in Tsleil-Waututh Nation is being seen as a partial victory for opponents to the pipeline. This decision will also likely result in some immediate delay on the project. However, the fact that the Government of Canada is the owner of the pipeline adds an additional dimension to the matter. Unlike a private actor, the Government of Canada has legislative tools at its disposal to ensure the project’s timely execution. Whether or not the Government of Canada chooses to use legislative tools to usher the project forward remains to be seen.